08 Dec A Passion of the Circus: A Journey Through History, Tradition, and Modern Communication

By Claire Le Meur, General Manager of Blue Bees

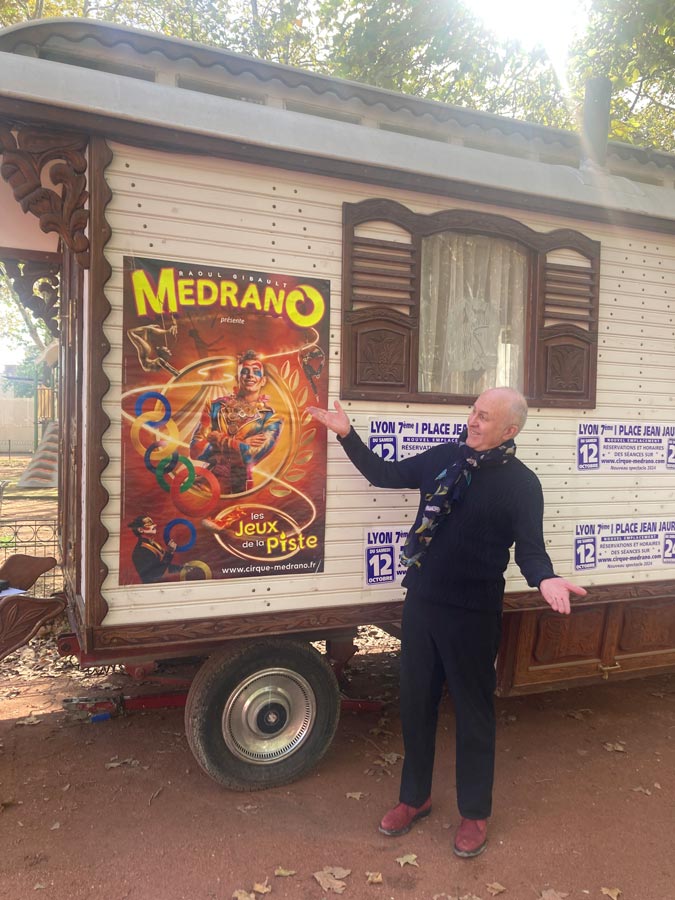

Since October 12, the Medrano Circus has returned to Lyon, as it does every year, to kick off its French tour with a new 1-hour and 45-minute show themed ” Games of the ring.” Leading the circus is a passionate man whose life intertwined with the circus more than forty years ago: Raoul Gibault. We met this fascinating individual, now at the helm of a globally renowned circus employing over sixty people.

Claire Le Meur: The new Medrano show tours eighteen cities across France until next May. That’s quite something! How do you communicate for this type of event?

Raoul Gibault: The circus is incredibly interesting when it comes to communication. For instance, there was a time when the great advertising directors, such as the head of Avenir Publicité, all had connections to the circus. That was the golden age of posters. I’m a big fan and collector of posters.

Today, posters are just one communication tool among many, especially with the rise of social media. Many fabulous artists—Capiello, Paul Colin, Kieffer—expressed themselves through posters. Nowadays, posters are rarely printed; they are mainly used on social media.

When I create a show, I start with the poster and visual concept. This year, Thierry Planès, the stage director who began working with me, contributed to the show’s design. He’s the creator of Mondoclowns, an internationally acclaimed clown festival in Marmande. Next year, he will take full charge of the production. Historically, Medrano has always been about clowns. Gruss was associated with horses, while Medrano’s history is deeply tied to clowns. I want to return to these roots, to authenticity.

There are no more animals, but for today’s audiences—especially young ones—we are introducing new codes: freestyle acts, BMX, laser displays, and more. When I was young, a circus’s grandeur was measured by the number of elephants. That’s no longer the case.

CLM: In our last conversation, you explained that horses were at the origin of the circus.

RG: Yes, the circus initially began with horse riders. Acrobats were later integrated. The clown emerged as an unlucky and clumsy acrobat who elicited laughter. Clowns appeared at the end of the 18th century, shortly after the circus began. The first circus in France was a wooden outdoor arena in Lyon’s Brotteaux district. These featured equestrian shows with acrobatics.

It is said that the first clown was a tailor who was finishing a rider’s costume. When the curtain rose, the horse bolted, leaving the tailor alone in the ring, making everyone laugh.

CLM: Is that a legend, or do you think it’s plausible?

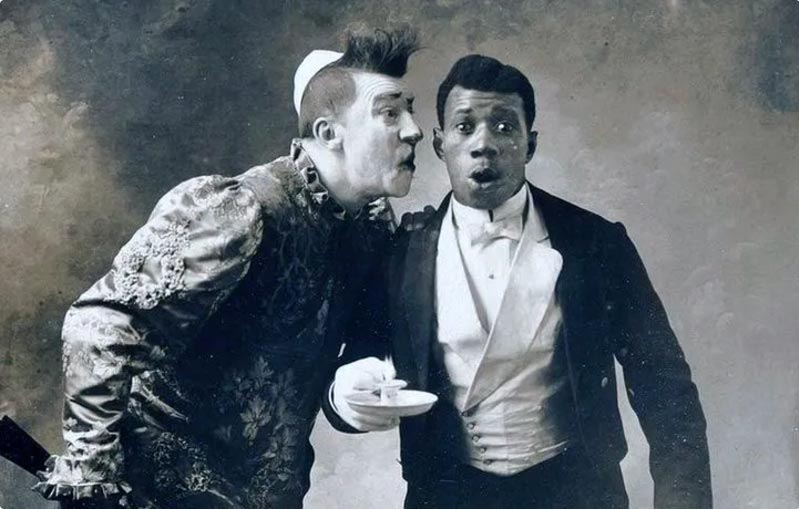

RG: I believe it’s true, although the story has probably been embellished over time. It’s similar to the beautiful film about the clown Chocolat. It’s romanticized. Chocolat was of Cuban origin and began life as a slave before being taken in by Geronimo Medrano.

In 1834, the circus program featured the clown Foottit performing solo in the first part, while Geronimo Medrano appeared in the second, accompanied by his clumsy Cuban servant who would unintentionally make the audience laugh. Foottit had the idea to make him his partner. Thus, Chocolat transitioned from being a servant to becoming an artist.

This duo made history. Some time later, Oller, the founder of the Moulin Rouge and the Olympia, built a circus on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, dubbed “Le Nouveau Cirque.” In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it became Paris’s favorite venue, being the first to use electric lighting. Foottit and Chocolat were the first clown duo to perform there. In the film featuring Omar Sy, the story was romanticized, but Chocolat remains one of the first Black artists.

CLM: Let’s talk about your story… How did Raoul end up joining a circus? That’s not a typical path.

RG: It can be summed up in two words: passion and perseverance. As a child, at four years old, I was taken to see the Amar brothers’ circus in Roubaix, in northern France. I was terrified of the clowns but fascinated by the world of the circus. Back then, the big tops were still made of cotton, which was much cozier than today’s plastic ones. There were the smells of animals, exoticism, and sawdust.

We live in an increasingly sanitized society, and smells are fading away. When I still had animals, young visitors would often comment on how bad it smelled. These were smells they were no longer accustomed to. For me, as a child, everything was magical: the scents, the big top, the lighting, and the ephemeral nature of it all. When the circus left, all that remained was a circle of sawdust. The dream had vanished.

I grew up in a gray region—the North. The circus was a ray of sunshine. I fell under its spell, even though I was scared of clowns. I knew immediately that I wanted to be a part of it. That desire never left me.

As I grew older, I would wake up at four or five in the morning to watch the first caravans arrive in the square. I made friends with circus people and started spending my vacations there. Although I wasn’t born into the circus, I feel like I’ve always lived in that world. I loved everything about it—not just the performances, which are just the visible tip of the iceberg, but also the arrivals, the setups, and everything else. I built connections and gradually managed to integrate into this world.

CLM: What did your parents think of all this?

RG: I come from a bourgeois background. My father was an ophthalmologist, and my mother was a university professor. My father and paternal grandfather would have loved to join the circus. When I was five or six, my grandfather even built me a miniature circus.

My mother, on the other hand, asked my father to stop taking me to the circus.

CLM: Was it becoming dangerous?

RG: [Laughs] Yes! Having a showman in the family was out of the question. I did just enough in school to pass. I spent hours daydreaming. I was very literary. Back then, you had to take a “Bac C” (science-focused baccalaureate), no discussion. I only passed because of my strength in literary subjects.

I read many books about the circus and the arts. That’s how I discovered Medrano. Medrano, with its Parisian roots in Montmartre (established in 1897), benefited from the renown of painters and writers like Lautrec, Picasso, and Léger, who all frequented the area.

By 1963, the Medrano Circus had disappeared from Paris, and I was born in 1964. I never saw the venue. My connection with Medrano comes through the works of these artists and writers who brought it to life for me.

At that time, the large traveling big tops belonged to the Amar brothers, Pinder, and the Rancy family. The latter were considered the aristocracy of the circus. They were equestrians at the court of Tsar Nicholas I in Saint Petersburg. Due to the Crimean War in 1854, they were forced to return to Europe, settling in Lyon with seventy or eighty horses.

This was the era when the circus created pantomimes—shows that told stories before the invention of cinema. These featured horses, acrobats, Napoleon, and his battles. This is why circus posters from the late 19th century look like anything but circus posters.

In 1856, Théodore Rancy founded the Rancy Circus in Lyon on Avenue de Saxe. It was called the Alcazar, a performance hall with an equestrian ring that immediately became successful. Later, the Alcazar was demolished to make way for a permanent circus. At the same time, he also built a permanent circus in Geneva. There were no caravans; they lived in apartments, like theater directors.

CLM: Does that mean they moved to different locations depending on their shows?

RG: Yes, they had apartments in the cities where they performed. That was how the circus operated at the start. But two external phenomena, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, disrupted everything: the arrival of Buffalo Bill and Barnum. Phineas Taylor Barnum created a theater of oddities, or side shows. The tours of Buffalo Bill and Barnum were major events.

Buffalo Bill showcased Native Americans, cowboys, and even elephants. Barnum, meanwhile, brought freak show attractions (dwarfs, Siamese twins, etc.) as well as exotic animals like giraffes and hippos.

This energized traveling menageries. Later, in rural areas where Barnum didn’t go, smaller menageries were created, featuring a lion, a wolf, or a hyena. These were housed in wagons. There was no training; a man would enter the wagon with a chair, and the audience would gasp, “Hoo, Haaa, Hoo, Haaa” [laughs]. People didn’t know these animals.

Meanwhile, in Russia, the Durov family established a place that combined a theater, a menagerie, and a laboratory to study animal behavior.

CLM: That really changed the game!

RG: Permanent circuses continued to operate, but the Rancy family, for instance, abandoned their Lyon circus in 1904. Around that time, horses had become symbols of wealth and were taxed heavily, which the family couldn’t afford.

The circus has always evolved in response to societal constraints and changes. It will always have a role to play on a human level. Circus communication has evolved too; what was once positive can now be a negative. For example, when a circus draws too large a crowd, it can intimidate local authorities.

CLM: How did you explain to your parents, after passing your baccalaureate, that you wanted to work in a circus?

RG: I passed my Bac at sixteen and knew I wanted to join the circus. I saw people in their forties and fifties who had given up on their dreams, and I didn’t want that regret. Circus families may exist, but it’s the newcomers who often bring evolution to the art.

For instance, the Court brothers created the first motorized circus in the early 20th century, even though their parents were wealthy nobles running one of Marseille’s largest soap factories. The circus was even called Barnum at one point because, once Barnum returned to the United States, no one was going to check…

CLM: Communication and information didn’t travel as fast back then as they do now.

RG: True, but I believed in my lucky star and knew I would only be happy if I pursued what I loved. The wealth of the circus world is immense.

The Medrano circus has a saying: “We came from every country, every religion, but we shared one faith.” That deeply resonated with me. I thought, What do I have to lose? If it works, I’ll be the happiest man alive. If it doesn’t, I can always return home, go back to school, and conform. But at least I wouldn’t have any regrets.

At that time, I was in law school, living in Pas-de-Calais, and I had a great advantage. I had friends who took me to Amsterdamand England to see foreign circuses. Every two weeks, I would visit a circus—I was at the crossroads of Europe. I told myself, “What do you have to lose? You join the circus, it works, and you’ll be the happiest man alive. If it doesn’t work? You’re the son of a bourgeois family—at worst, you go back home, resume your studies, and fit into the mold. But at least you won’t be frustrated.”

At that time, I was in law school, 18 years old, and living in Pas-de-Calais. I was incredibly fortunate—I had friends who took me to Amsterdam and England to see foreign circuses. Every two weeks, I went to a circus—I was at the crossroads of Europe.

This deeply annoyed my mother, who told me bluntly, “Your exams are in two months, so the weekend getaways are over. Now, you study.” I replied, “I’m 18.” And she said, “What difference does that make? As long as you live under our roof, you follow our rules.”

So I told her, “If that’s how it is, I’ll pack my bags and leave.” She called my grandfather, a philosophy professor. He told her to let me go and have my experience. So they let me leave, and I arrived at a friend’s circus, where I had occasionally spent weekends.

They were surprised to see me arrive with my suitcase, as it wasn’t the weekend. I explained that I was now moving into the circus, without really knowing what I was going to do. I was gone… left…

CLM: What was your first job at the circus?

RG: I was part of the assembly crew. I helped set up the big top. Very quickly, I took on responsibilities for advertising and communication. It was very different back then. I would go to a phone booth with a bag of coins and spend my days calling towns to secure agreements.

Before long, I became the one organizing the tours. I helped with ticket sales, took part in all kinds of tasks, and immersed myself in circus life. I shared a bunk with a Moroccan colleague who also worked at the ticket counter. I had no money, I had nothing, but I was so happy to finally be there.

I caught the attention of Edelstein, who would later buy all of Jean Richard and Pinder’s circuses. He offered me a job as a “front-runner.” This involved arriving in a town about two weeks ahead of the circus. I would visit prefectures and city halls, deliver invitations, and meet with journalists and press correspondents. This practice no longer exists today.

I completed a tour like that with Pinder, which was incredibly enriching, but living alone in a caravan, ahead of the circus, wasn’t ideal for me. I had to negotiate with people for electricity hookups, and I had no running water, so I showered at public pools. It wasn’t easy, though I have fond memories of it. I learned the trade, but the pay was terrible.

After a year, I approached Edelstein and told him I wanted to do something different. When he refused to offer me another role, I decided to quit. Returning home was absolutely out of the question.

CLM: You didn’t want to fulfill the prophecy [laughs]…

RG: Exactly! Through a friend, I got in touch with the Charles Michaelis organization, which managed all the Holiday on Icetours. They offered me the chance to help organize their six tours. I was intrigued because I already had the idea of starting my own circus.

A circus, after all, is a team—it’s a company that involves transportation, setup and teardown, advertising, and the show itself. There was no way I could do it all alone overnight. It would take years to build a team and surround myself with the right people.

I found it fascinating to observe the economic model of Holiday on Ice, which performed in indoor venues. I was responsible for press reception, ticketing, reservations, and scheduling. Back then, ticketing was still manual; we marked seats on a physical plan. I stayed in hotels and acted as the right-hand man to Jean-Yves Gérard.

We would arrive in cities three weeks before the show. In three months, I worked in three cities: Valence, Lyon, and Grenoble—all in sports arenas. It was an American organization, but I was employed by the French subsidiary. The rules were very strict: I was not allowed to have any contact with the artists.

After three months, I was summoned to the Paris office and informed that a one-year contract was being prepared for me. I told them I didn’t intend to continue. That was a shock to them. I found the logistics, organization, and venue operations interesting, but it wasn’t the circus.

At that point, I had three interviews. The first was with Alexis Grüss at the National Circus, but it didn’t click at all. The second was with Christian Taguet at “Le Puits aux Images.” It was nice, but a bit too laid-back [laughs]. They didn’t tour, only performed three shows. Then I met Annie Fratellini. It was a bit chaotic—she had forgotten we had an appointment. This was in 1984 or 1985.

CLM: Where was Annie Fratellini’s circus located at that time?

RG: At La Villette. She had two ventures: her school and a small touring circus featuring her students, which ran for six months and was part of cultural programming. But she struggled with this circus. She was immensely talented but not a manager.

She offered me the role of organizing tours and preparing for the circus’s arrival in different towns. It was a fantastic opportunity. It was a small circus but one with a real soul. She had a gift for placing the right people in the right roles based on their skills. I spent two exceptional seasons there.

Meanwhile, since 1982, we were fortunate to have Jack Lang as Minister of Culture. He restored the status of the circus, as well as comics, to their former glory. His cultural policy was built on three axes: the National Circus (entrusted to Alexis Grüss through Sylvia Montfort), the creation of the National Circus Arts Center in Châlons-en-Champagne, and STEP, a structure tasked with managing other circuses, chaired by the deputy-mayor of Valence, Rodolphe Fraysse.

In 1982, he organized a conference to which the Rancy Circus, where I was working at the time, was invited. This gave me the opportunity to meet Jérôme Medrano, who had left the Montmartre circus in 1963. The lease had expired, and he didn’t have the means to buy the venue. He became a tenant of his competitor Bouglione, who had already purchased the Cirque d’Hiver.

Medrano moved to Monaco, where Prince Rainier entrusted him with the artistic direction of the Société des Bains de Mer. However, his relationship with the principality was strained due to his strong personality. He was a genius and consistently had incredible ideas until his death in 1998. He was the first to install electricity in a circus, the first to use colored lighting, and much more. To me, he is comparable to Jérôme Savary. He was willing to take enormous risks to produce a show.

CLM: That must require a touch of madness and a bit of a temper…

RG: Yes, they were temperamental characters but truly visionaries. When I met Jérôme Medrano, he was a dreamer. He envisioned a circus with five thousand seats. I, on the other hand, wanted to start from scratch.

My dream was to produce a show in Italian-style theaters with all their decorum and ambiance. While working with Fratellini in cultural venues, I realized there were people who attended the circus but would never set foot in traditional cultural spaces.

In 1987, I decided to stage circus performances indoors, preferably in venues with a soul. I convinced theater directors by explaining how this could help different audiences discover or rediscover the circus.

For the first tour, I worked alone. I was fortunate to secure some funding through two avenues: first, the Jacques Douce Foundation (founded by the creator of Havas), which supported innovative and ambitious projects. I was one of its laureates.

This allowed Avenir to offer me a year-long advertising campaign, and Air Inter provided me with a year of travel vouchers to plan and prepare my tour. I managed my first three tours this way.

CLM: What was the name of your first show?

RG: At first, Medrano didn’t want his name associated with it because it wasn’t traditional circus. I managed to convince him by proposing the idea of not calling it “Cirque Medrano” but rather “Medrano, Like the Circus.” He laughed, called me quite the character, and agreed.

After three years, a problem arose: cultural programming requires renewal, which isn’t the case with the circus. In the circus, there’s a tradition of returning. I had to turn to different venues. Fortunately, this was the time when Zénith venues were opening. I don’t particularly like them because they’re multipurpose spaces.

CLM: Venues where you can do everything but really nothing…

RG: Exactly. But it was an opportunity. We filled the venues. It allowed us to choose our dates, to come back each year at the same time. But artistically, no matter how much I tried to adapt my shows, the atmosphere wasn’t the same.

In 1996, now that I had built a team and gained experience, I returned to big tops. From a one-year contract, Jérôme signed me on for five years. Now, I’m the one carrying the Medrano name forward while starting to prepare for the future. I want it to continue and endure.

CLM: How do you handle communication for the new show that just arrived in Lyon? Do you still use posters? Do you communicate on social media?

RG: We use social media a lot.

CLM: And how many people work for Medrano in total—artists, technical, and administrative staff included?

RG: Around sixty people. At our peak in 2014, we had up to 450 employees. We had seven big tops touring, 290 vehicles, and nearly a million spectators annually. It was a massive operation.

In 2015, during the terror attacks, I had one big top in Lyon, and the others were about to start their tours. I received a call from the prefecture warning me that it might not be safe to open my circuses. That scared me.

I realized it was a giant with feet of clay. The whole structure rested on very little. Fortunately, I had that realization because what followed—yellow vest protests, COVID, the end of animals in circuses—was even more challenging.

I began to gradually “land the plane,” knowing that the descent was almost more perilous than the ascent, and I wanted to do it without any shocks.

Today, I only have one show touring. In December, there’s a second circus that performs the previous year’s show. From 250 cities a year, we’ve reduced to 25–26 cities. We’ll continue downsizing, partly because itinerancy has become too large a part of the budget—it’s too costly.

Like the restaurant industry and many other professions, we also face staffing challenges. Fewer people are willing to work weekends. The economic model is constantly evolving. We might even return to a semi-fixed circus model.

CLM: How do you see the future of the circus?

RG: In the past, large circuses traveled to towns near Lyon, like Vienne. Now, it’s only small family circuses with animals that still tour.

CLM: How are they still allowed to have animals?

RG: Because the official decree only makes the removal of animals from circuses mandatory in 2027. We preferred to anticipate the issue. Moreover, we want to maintain long-term partnerships with cities—I don’t want to find myself in a situation of conflict.

CLM: How long will your new show run? And how many people do you host on average per performance?

RG: The circus will be performing in Lyon until November 24. This weekend, we had three sold-out shows on Saturday—we have 1,447 seats. So, we welcomed 4,200 people. On Sunday, 3,000 more attended. In total, over 7,000 people came to see the show during the opening weekend. We also have reserved evenings and visits from youth centers.

CLM: With an enterprise of this scale, it’s no longer the image of “wandering performers” with gypsies and caravans…

RG: No, that’s precisely the challenge with the circus’s image. We are a business like any other. We pay social security contributions, taxes—it’s only normal. We’re somewhat in a phase of regression, like in the 1980s. But I’m convinced things will reverse starting in 2030. People will rediscover the circus.

It’s also worth noting that larger structures like ours have moved on and anticipated these changes. However, there are still family circuses pushing forward with animals, which don’t always present a positive image of the circus. But you can’t blame them—it’s the system that creates these circumstances.

I was part of the group invited to the Élysée in 2021 to discuss the circus and the issue of animals. Certain sacrifices had to be made to address ecological concerns. Regarding animals in circuses, it’s important to note that there was a circus before wild animals. Barnum introduced the menagerie circus, but it was just one phase of the circus’s history.

This shift is also a reflection of life’s evolution. For example, animal trainers lived 24/7 alongside their animals. There were no vacations—it was a passion but also a calling. The new generation no longer has the same desires.

There’s also the question of troupes. We live in a society where individualism has grown. This lifestyle and way of operating don’t necessarily have an immediate future. The circus will reinvent itself.

CLM: In your opinion, were the animals happy in circuses?

RG: I believe they were happy. I’m against taking animals from their natural habitats because it causes psychological trauma. I didn’t live through that era in the early 20th century. But an animal raised in captivity with humans is a different story.

In Thailand, for instance, the Asian elephant has always been used for transportation and agriculture—just like the horse in Europe.

Of course, not everything is perfect, as in any profession, but I’ve witnessed beautiful relationships between humans and animals.

I knew there would be fewer and fewer people in my circus willing to care for animals. In France, there are currently 600 to 700 captive felines in small circuses, traveling everywhere, even to challenging suburban areas.

By 2027, there will only be about 120–150 spaces in sanctuaries to accommodate these felines. For the remaining animals, euthanasia is being considered.

In 2022, I was responsible for 177 animals. I was the last in France to have elephants, and I was under intense scrutiny.

I managed everything to ensure the animals ended up in good living conditions. The zebras went to Germany; the llamas and zebus were easily placed in educational farms. My elephants went to England, to Buddhist monks at a Hindu sanctuary.

Elephants are not easy—they decide whether or not they accept the person who will care for them. They followed us like dogs… The monks came several times over fifteen days to ensure the elephants accepted them.

CLM: That’s surprising—England… Does the climate work for elephants? Isn’t it too cold?

RG: No! Contrary to what people think, in Asia, in the forest, it gets cold at night. Asian elephants aren’t afraid of the cold. However, they suffer if there isn’t enough humidity, so the English climate is suitable. My elephants retired there—they were at least 67 years old.

I also had 24 tigers. During COVID, one of my young team members, who was passionate about animals, took care of them. I had received offers to sell them to Dubai, which I obviously refused because of my love for animals. A few years earlier, he had found a family in the southwest of France who owned a wooded area with a cave that they opened to tourists, along with farm animals.

They had invited him to come during the summers to offer educational presentations about the lives of these animals. He spent two summers there, which went very well. When I decided to part ways with the animals, I proposed that he take on the tigers and find a more sedentary activity where he could continue caring for the big cats.

It’s still possible to have a stationary activity with animals, thanks to Philippe De Villiers, who fought for the authorization to keep captive animals in fixed locations. He contacted his friends, and my team member moved there with the tigers. The facilities were approved by the Ministry of Ecology, as well as his professional capacity to care for the animals. The tigers are doing well.

CLM: One last question… What do your parents, who once saw you as a wandering performer, think of the business leader you’ve become?

RG: My father has passed away. I believe he was proud, even if he didn’t show it much. My mother is 87 years old. We have a good relationship now. But compared to my brother, who went to Sciences Po, it still seems less prestigious to her.

Even though I achieved up to €15 million in annual revenue in 2014 and still generate €3–4 million per year now after choosing to scale down my business, she doesn’t see it the same way.

Now, I’m focused on the future because I want this circus to continue after I’m gone. There will always be a need for the circus and for direct interaction with people—beyond everything virtual. I’m optimistic! We play a social role.

That’s why we’re currently working on our next show—and, of course, its poster—centered around the theme of love.

CLM: Do you plan to retire?

RG: No! No, because I’m nothing without this…

CLM: Like all circus artists, will you die on the ring?

RG: Not on the ring, but not far from it… I think my Moldovan friend, with whom I’ve worked for fifteen years, will take over. He is as passionate as I am. I’ve already started the transition phase, but I don’t plan on retiring. I love what I do too much.

I also have a dream: I probably own one of the largest collections of circus posters, and I’d love to be able to display them one day…

The Bees extend their best wishes for success to the Medrano Circus team and their new show! A huge THANK YOU to Raoul Gibault for taking the time to share this extraordinary story.